Is this America's next foreign policy objective?

Recent sanctions relief for a powerful financier in Cyprus raises questions about American desires to rid the island of Turkish influence.

The Trump administration quietly removed economic sanctions against a top Russian oligarch’s financial fixer from Cyprus in late November.

Demetrios Serghides is believed to have managed the money of Alisher Usmanov, a billionaire whose wealth stems from his partial ownership of the Moscow-based mining and steel company Metalloinvest.

The U.S. first cut off Serghides from the American banking system in 2023, when the Department of the Treasury — alongside its counterpart in the United Kingdom — announced new sanctions against 25 of Usmanov’s closest allies and business partners.

While the Biden administration loudly announced those sanctions, the recent removal of Serghides from the sanctions list on November 26 came with no official explanation from the White House.

But this financier’s background and the timing of the sanctions removals may be illuminating.

In addition to freeing up the financial blockade against Serghides, Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) also granted relief to a handful of powerful Cyprus-based organizations and individuals tied to Serghides.

This all might be the earliest signs of the Trump administration pushing for an agreement to end the Turkish occupation of Cyprus in order to open up energy opportunities in the Eastern Mediterranean. Stick with me.

THE BACKGROUND

Cyprus is an island nation tucked in the Mediterranean Sea just south of Turkey and west of Syria.

The British ruled there until independence in 1960. Soon after, the island launched into a downward spiral fueled by ethnic tension.

The population of Cyprus is split between a Greek majority and a Turkish minority. For decades, both parent countries— bitter rivals as they are— tried to steer the island into each of their orbits.

In 1974, Greek forces attempted a coup. Turkey then invaded soon after, taking control of a third of the island which it still controls today.

The result is a split nation. The Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus is dug in to the north and the Greek-speaking Republic of Cyprus governs the south. The capital city of Nicosia is cut in half by the UN-administered green zone.

On paper, the United States and its allies in Europe only recognize the Republic of Cyprus, considering the Turkish breakaway state to be illegitimate. Sectarian violence on the island is rare, but a permanent solution to de facto division remains out of reach.

WHAT’S NEXT

It would be irresponsible to say the United States lifting sanctions on several Cypriot nationals and organizations is a sure sign of the Trump administration’s increased involvement in the island.

But could it fit into a pattern?

There is at least some interest in Washington in getting the Turks out of Cyprus. Just before President Trump’s second inauguration in January, a bipartisan group of four Greek-Americans in the U.S. House of Representatives introduced a resolution urging Trump to solve “the Cyprus problem,” calling it “a top foreign policy priority.”

Then, in October, Trump nominated a new ambassador to the island, John Breslow. Cypriot media is picking up on something as well. Politis, one of the central Greek-language newspapers in Cyprus, published an article in November predicting a forthcoming U.S. proposal to remove the Turkish military from Cyprus as part of a larger move to access energy resources in the Eastern Mediterranean.

The interest in changing the political landscape of Cyprus is likely not rooted in a moral cause, but rather in practical American energy objectives.

With new sanctions on Russian oil and the general desire to get Europe off of Moscow’s energy, the Trump administration has championed a number of natural gas projects in the eastern Mediterranean. One, the Vertical Gas Corridor, provides a route for transporting liquefied natural gas from Greece to eastern Europe, bypassing Russian sources.

In a brief published this August, the United States Energy Association presented the corridor as “a viable alternative to Russian gas.”

In November, the energy ministers of Cyprus, Greece, and Israel met with U.S. government officials in Athens. Following the talks, they released a joint statement in support of “broader regional interconnectivity projects, currently in progress and future ones.”

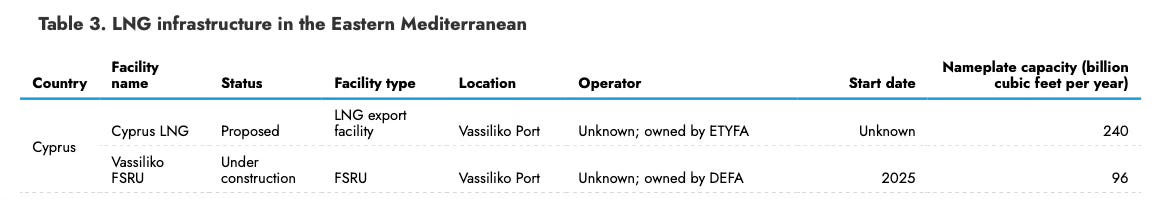

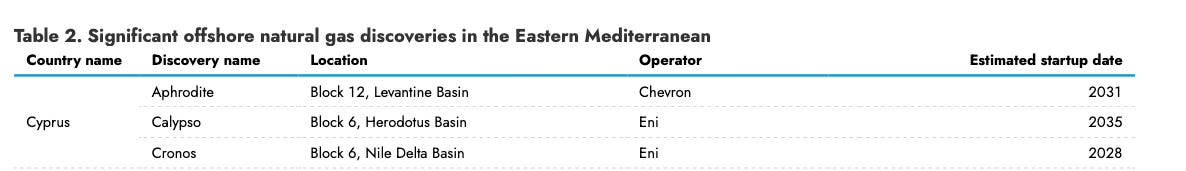

This all comes years after the first Trump administration pushed for an even larger Eastern Mediterranean Gas pipeline, which would harness new LNG discoveries in Cyprus. In fact, construction on the island’s first piece of LNG infrastructure began this year (see below).

However, Turkey is getting in the way. A report from the U.S. Energy Information Administration in September noted that territorial disputes between Turkey and the Republic of Cyprus have created difficulties for the prospect of bringing the Eastern Mediterranean Gas pipeline to life.

Perhaps freeing up the entire island from Turkish influence could accomplish American energy goals in the region and lessen dependence on Russian energy in the long term.

The formerly-sanctioned Serghides could prove a link between Cyprus and Russia that could aide the U.S. in diplomatic efforts on the island.

Whether this is the reason the Department of the Treasury decided to remove sanctions on him and his associates remains to be seen.

For now, one thing is certain: watch for U.S. moves in Cyprus.